1. Overview.

The visual system of the goldfish has been the subject of intensive studies for over a quarter of a century. It differs from the visual system of most other vertebrates, including mammals, in that it continues to grow by the addition of new neurons throughout much of the animal’s life. This unusual characteristic has presented the neuroscientists with an opportunity to examine how the existing visual pathway accommodates the new growth, for example as the axons of the newly born retinal ganglion cells exit the eye to join the older axons in the optic nerve tract – a conduit that carries visual impulses from the retina to the brain. Furthermore, for largely unknown reasons, the visual system of the goldfish is endowed with the capacity for repair if injured, culminating in the recovery of vision. Much research has been undertaken to identify the cellular and molecular components that support this phenomenon, not least because the knowledge gained may be helpful in the quest to understand why a similar injury in the mammals and Man invariably leads to an irreversible loss of function.

The following commentary is a pictorial journey through the visual system of the common strain of the goldfish (Carassius auratus). It highlights, by the use of species-specific immunocytochemical markers and electron microscopy (EM), the system’s many unique structural features which are quite unlike those in other vertebrates, and are thus of interest because of the likelihood that they reflect a patterning better suited for the restoration of its cytoarchitecture post injury.

In this commentary I first describe the organisation of the normal goldfish visual system, and point to those features that distinguishes it from the visual system of other vertebrates. This will be the foundation for the main theme of the commentary, in which I describe some of the cellular events that accompany the process of repair in the injured optic nerve of the goldfish.

2. General Features of the Goldfish Visual System.

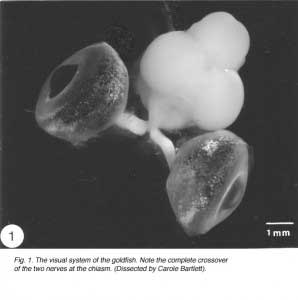

Like the brain and the spinal cord, the visual system of the vertebrates is a component of the central nervous system (CNS). In the goldfish, the visual system is made up of three distinct compartments (Figure 1). (1) The retina, which lines the posterior of the eye. Axons of retinal ganglion cells emerge from the back of the eye, acquire myelin sheath and become grouped into bundles, thus forming (2) the optic nerve. The two optic nerves cross bodily at the midline – a region known as chiasm – where they enter the skull to join (3) the tectal target in the brain contralaterally, not ipsilaterally as in most other vertebrates. Thus, axons of retinal ganglion cells represent the only structure that is common to all three compartments, which are, nevertheless, distinguished by different types of astrocytes, or astroglia cells, which form the principal framework, locally adapted to serve the needs of the tissue, as described below.

3. Astrocytes in the retina.

3. Astrocytes in the retina.

The Muller cells are the principal glia (Latin: glue) cells of the teleost retina. They form architectural support structures stretching radially across the thickness of the retina. At the turn of last century, Cajal (1989 ) described the fine structure of Muller cells in several species using Golgi staining, a technique which bathes the tissue in silver salts to reveal the fine details of individual cells. The Muller cells bodies lie in the inner nuclear layer of the retina, and project thick and thin processes in either direction to the outer and inner limiting membranes. Muller cell processes insinuate themselves between cell bodies of neurons in the nuclear and plexiform layers, and enwrap neuronal cell bodies (Reichenbach, 1989). Through this extensive system of cell processes, Muller cells are believed to provide metabolic support to the retinal neurons, as well as remove their waste.

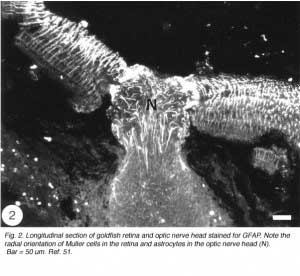

The Muller cells are considered to be a type of astrocytes because their processes are filled with intermediate filaments – so-called because their diameter is intermediate between myosin filaments (15 nm) and actin filaments (6 nm) – that stain dramatically with antibodies to GFAP, the subunit protein of the filaments found in astrocytes (reviewed by Traub, 1985). The GFAP subunit is well conserved across the vertebrate phylum, and in goldfish, as in rat, it has a molecular weight of 51K, as determined by SDS-polyacrylamide elctrophoresis (Nona et al., 1989). The antiserum to goldfish GFAP, when applied to sections of goldfish retina, specifically recognises Muller cells’ radial processes which at the basal end enwrap retinal ganglion cells perikarya and form end-feet at the vitreal surface of the retina, whilst at the other extremity they elaborate a network of fine processes that terminate at the photoreceptors (Figure 2). The Muller cells perikarya and lateral processes, both of which are readily seen by the Golgi method, are not revealed by anti-GFAP, possibly because these structures do not contain GFAP in detectable amount. Nevertheless, the specificity of the antiserum is nicely demonstrated by the absence of staining elsewhere in the retina. In this context it is interesting that “free” astrocytes, of the type described in the nerve fibre layer of mammalian retina (Schnitzer, 1988), are absent from the teleost retina.

4. Astrocytes in the optic nerve.

4. Astrocytes in the optic nerve.

The structure of the fish optic nerve has been described by several workers using various methodologies (Easter et al., 1981; Levine, 1989; Maggs and Scholes, 1990). This author intends to add another dimension to these reports, by describing the pattern of glial cells and optic fibres in the normal goldfish optic nerve as revealed by goldfish-specific antibodies to GFAP and neurofilament protein, respectively. These studies are complemented by ultrastructural studies to provide a detailed picture of the optic nerve structure and, therefore, a template with which to compare the structure of the repaired nerve following injury.

In the goldfish, the optic nerve is cylindrical in shape, measuring 0.5mm in diameter and 2.5mm in length (in a 5cm long fish). The optic nerve is white in appearance on account of the lipid-rich myelin sheath that enwraps its fibres (see Figure 1). For the purpose of this discussion, the optic nerve will be divided into two parts: (a) the intraocular optic nerve, and (b) the intraorbital optic nerve, through to chiasm.

The intraocular optic nerve

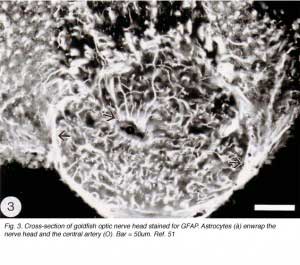

The tip of the optic nerve, which lies within the retina, has a conical shape. Axons of retinal ganglion cells converge onto the optic disc to be funnelled into the optic nerve head by a resident population of GFAP+ astrocytes whose radial orientation corresponds to the trajectories of the axons (Figure 2). This arrangement implies that astrocytes at the optic nerve head direct the axons away from the rest of the retina and into the optic nerve head, perhaps through the expression of a combination of attractant and repellant molecules on their surface (Dingwell et al., 2000; Stuermer and Bastmeyer, 2000). Astrocytes, additionally, envelop the surface of the optic nerve head in a characteristic fashion known as glia limitans, thus forming a tube-like structure through which the axons are funnelled (Figure 3). Running through the centre of the optic nerve head is the central artery, which is also enwrapped by astrocyte processes. It is thus reasonable to assume that the manner with which the astrocytes envelop the vasculature and the axons signifies some primitive disposition of blood-brain barrier, as well as providing a nutritive service, much like the Muller cells in the retina.

After the optic nerve leaves the retina and passes through the globe’s outer layer, the sclera, its tightly packed fibres more than double in size as they enter the orbit. This transition is a landmark, for it signifies that the hitherto naked fibres have acquired myelin sheath. Thereafter, the glial cells sculpt the optic nerve into an intricate pattern, the fine details of which are beautifully revealed by immunocytochemistry.

An unexpected finding, reported nearly simultaneously by several laboratories, revealed that astrocytes in the normal fish optic nerve do not contain an appreciable amount of GFAP (Nona et al., 1989), the universal marker for astrocytes (Bignami, 1991). Rather, astrocytes of goldfish optic nerve (Fuchs, 1994, Levine, 1989) and cichlid optic nerve (Maggs and Scholes, 1990) are composed largely of cytokeratin polypeptides – proteins that are normally found in epithelial tissue. This finding led some workers to propose that the absence of GFAP is a reflection of the immaturity of the tissue and is, therefore, the reason why fish optic nerve has the capacity for robust regeneration (Fuchs 1994). However, this suggestion has been mooted by the author and his colleagues, who were the first to demonstrate that the attenuated level of GFAP in the goldfish optic nerve (Stafford et al., 1990) is greatly enhanced following an injury to the visual system (Figure 4).

Interestingly, the dramatic response of fish optic nerve astrocytes to injury, whilst in keeping with what is generally observed in all damaged CNS tissue, was to be followed by more dramatic cellular responses in the optic nerve that set this tissue apart from its mammalian counterpart, and offered an explanation for its spontaneous recovery post injury.

Interestingly, the dramatic response of fish optic nerve astrocytes to injury, whilst in keeping with what is generally observed in all damaged CNS tissue, was to be followed by more dramatic cellular responses in the optic nerve that set this tissue apart from its mammalian counterpart, and offered an explanation for its spontaneous recovery post injury.

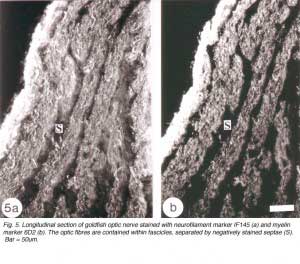

The response of the goldfish optic nerve to injury reveals a striking pattern underlying the tissue’s framework: it shows that the first one-quarter of the optic nerve is made up of GFAP+ astrocytes that are organised as a dense, lace-like pattern with no evidence of segmentation into discrete domains, an observation that is reflected in the organisation of the fibres which appear closely bundled, with no discernible spaces between them (Nona et al., 1990). Further along the nerve, however, up to the nerve-tract boundary, myelinated axons are organised into discrete domains, known as fascicles (Figure 5). In longitudinal profile, the fascicles appear as linear channels or tubes bound by parallel astrocyte processes (glia limitans), and each fascicle is separated from its neighbours by parallel rows of connective tissue septae. The pattern shows greater intricacy in transverse profile, with the astrocytes-bound fascicles being further divided into smaller compartments by fine processes (Figure 6), a pattern that is also seen with an antibody to goldfish cytokeratin (Levine, 1989).

Ultrastuctural studies of the optic nerve are in complete agreement with these observations (Nona et al., 2000; see also, Easter et al., 1981). They show the optic nerve to be made up of bundles of myelinated axons enclosed by astrocyte processes, thus forming discrete fascicles that are separated from adjacent fascicles by septae, containing collagen, fibroblasts and capillaries. Furthermore, each fascicle is divided into smaller compartments by astrocyte processes that form characteristic desmosomal junctions. The close correspondence between ultrastructural and immunocytochemical findings is depicted in Figure 6.

Ultrastuctural studies of the optic nerve are in complete agreement with these observations (Nona et al., 2000; see also, Easter et al., 1981). They show the optic nerve to be made up of bundles of myelinated axons enclosed by astrocyte processes, thus forming discrete fascicles that are separated from adjacent fascicles by septae, containing collagen, fibroblasts and capillaries. Furthermore, each fascicle is divided into smaller compartments by astrocyte processes that form characteristic desmosomal junctions. The close correspondence between ultrastructural and immunocytochemical findings is depicted in Figure 6.

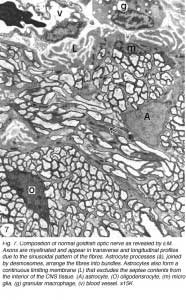

EM analyses additionally reveal that the optic nerve contains microglia, which equate to the macrophages normally found in the PNS, and become phagocytic if the tissue is damaged, as well as a unique class of non-phagocytic granular cells that reside normally within the sheath/septae. A full complement of the cells and structures that make up the goldfish optic nerve is given in Figure 7.

It is instructive to return briefly to the epithelioid characteristics of the fish optic nerve by referencing the cichlid optic nerves, which are formed as ribbons rather than discrete fascicles seen in the goldfish. The tissue pattern in the cichlid optic nerve appears to be more elaborate, with the longitudinally oriented astrocyte processes being connected at regular spacing by a lace-like network of finer astrocytes processes, laid out as sheets running at right angles to the optic fibres. Scholes and colleagues have proposed that this astrocytic pattern is linked throughout with desmosomal junction, thus providing the fish optic nerve with mechanical resilience needed during rapid eye movement. Astocytes in the cichlid optic nerves have been described as reticular astrocytes because they form a network pattern that complements the wavy pattern of the optic axons, enabling them to accommodate small stretches reversibly in a concertina-like action (Scholes et al., 1992). And, as if to emphasise that eye movement in the fish can only be accommodated by a framework made up of an atypical phenotype (epithelioid) astroglia, both in terms of its organisation and protein composition, the domain of the cytokeratin expressing astrocytes in the optic nerves comes to an abrupt end at the nerve-tract boundary, beyond which, and throughout the brain, astrocytes are typically of radial morphology and express GFAP only (Nona et al., 1989; see later).

It is instructive to return briefly to the epithelioid characteristics of the fish optic nerve by referencing the cichlid optic nerves, which are formed as ribbons rather than discrete fascicles seen in the goldfish. The tissue pattern in the cichlid optic nerve appears to be more elaborate, with the longitudinally oriented astrocyte processes being connected at regular spacing by a lace-like network of finer astrocytes processes, laid out as sheets running at right angles to the optic fibres. Scholes and colleagues have proposed that this astrocytic pattern is linked throughout with desmosomal junction, thus providing the fish optic nerve with mechanical resilience needed during rapid eye movement. Astocytes in the cichlid optic nerves have been described as reticular astrocytes because they form a network pattern that complements the wavy pattern of the optic axons, enabling them to accommodate small stretches reversibly in a concertina-like action (Scholes et al., 1992). And, as if to emphasise that eye movement in the fish can only be accommodated by a framework made up of an atypical phenotype (epithelioid) astroglia, both in terms of its organisation and protein composition, the domain of the cytokeratin expressing astrocytes in the optic nerves comes to an abrupt end at the nerve-tract boundary, beyond which, and throughout the brain, astrocytes are typically of radial morphology and express GFAP only (Nona et al., 1989; see later).

Taken together, the above results demonstrate that astrocytes in the fish optic nerve express both cytokeratins and GFAP intermediate filaments, in contrast to the mammalian optic nerve astrocytes, which express GFAP only. One possible explanation is that astrocytes may have a relict evolutionary status (Rungger-Brandle et al., 1989). For example, the most primitive of extant vertebrates, the cyclostomes, have astroglia with similar cytology throughout the CNS, showing dense intermediate filaments linked with desmosomes (Bertolini, 1964). Scholes has suggested that fish optic nerve has retained elements of an ancient glial pattern which became outmoded as the CNS became armoured in bone, but still appropriate in the orbit (Scholes et al., 1992).

5. Astrocytes in the brain.

Just beyond the chiasm, at the optic nerve-optic tract boundary, astrocytes phenotype changes abruptly in two respects: firstly, whereas before astrocytes were of reticular morphology, now they have a radial morphology. Secondly, whereas reticular astrocytes expressed strongly cytokeratin proteins and only faintly GFAP, radial astrocytes show a pronounced expression of GFAP and there is an absence of cytokeratins expression (Levine, 1989; Nona et al., 1989; Nona, 1995).

Astrocytes in the optic tract

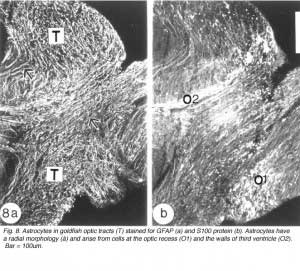

Astroytes in the goldfish optic tract appear to arise from two sources. The radial astrocytes that are seen at the commencement of the tract arise from cells whose perikarya line the optic recess. Evidence for this comes from the staining pattern of two adjacent sections of the optic tract, with anti-GFAP and anti-S-100 protein, respectively. Whilst the former marker recognises a profusion of radial processes, the latter additionally highlights a population of brightly stained round cell bodies at the nerve-tract boundary, extending into the optic recess (Figure 8). The validity of S-100 protein as a marker for astrocytes has been documented for mammalian astrocytes (Ludwin et al., 1976; Ghandour et al., 1991).

The second source of astrocytes in the optic tract are the cells that line the walls of the third ventricle, from where one subpopulation of radial astrocytes runs along the dorsal aspect of the tract, parallel to the optic fibres, whilst a second population of radial astrocytes traverses the tract to terminate as end-feet on its surface. Where the optic tract bifurcates, at the nucleus rotundus, before it joins the optic tectum, radial astrocytes are no longer discernible immunocytochemically (Nona et al., 1989).

Astrocytes in the optic tectum

Astrocytes in the optic tectum

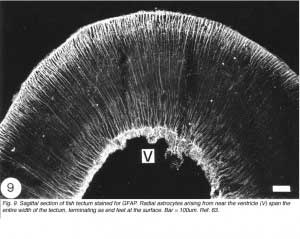

In the optic tectum of the teleost, there are two distinct populations of GFAP+ astrocytes. The ependymal region contains an extensive meshwork of astrocyte processes that border on the ventricular margin, and extend dorsally towards the neuronal stratum periventricular layer (Nona et al., 1989). Arising prominently from this region, and extending across all of the tectal layers, is a well-organised system of radial processes that terminate as end-feet on the pia surface (Figure 9). There has been much debate as to the source of these two astrocyte populations, with some authorities suggesting that they arise from a common cell body (Kruger and Maxwell, 1967). However, studies conducted by the author, using anti-S-100 protein, have revealed two distinct populations of cell bodies: one that is scattered in the ependymal region, and another, one or two cells deep, that is interposed between the ependymal and the stratum periventricular regions. It is from this second population of perikarya that fine radial processes emerge to traverse the tectum (Nona et al., 1989; Rabe et al., 1999), a finding that is supported by EM studies (Stevenson and Yoon, 1982). A curiosity is that in fish, neither the astrocytes in the brain nor those in the optic nerve conform to the classical description of astrocytes.

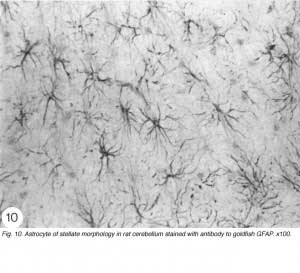

Strictly speaking, astrocytes are the star shaped GFAP+ glia cells (Figure 10; Shehab et al., 1989) in the adult mammals and birds, which have end-feet on CNS blood vessels (for an excellent review, see Bignami, 1991). They lack desmosomes and they appear late in development by proliferation of radial glia, following withdrawal of the pial and ependymal contacts (Schmechel and Rakic, 1979). In the fish, on the other hand, GFAP+ glia cells in the brain (Nona et al., 1989) and spinal cord (Nona and Stafford, 1996) retain their radial morphology in the adult. The persistence of radial astrocytes may signify some dependence on cell contact with the ependymal lining of the CNS ventricle. The absence of the ependymal structure from the optic nerve of the fish, therefore, explains nicely why astrocytes here differentiate as a specialised form – the reticular astrocytes (Scholes et al., 1992).

6. Axon regeneration in injured goldfish optic nerve.

6. Axon regeneration in injured goldfish optic nerve.

The literature abounds with studies that confirm an observation made by Ramon y Cajal (1928) almost a century ago that, with a few exceptions, severed axons of the neurons in the mammalian CNS are capable only of abortive sprouting that provides little functional recovery. In contrast, neurons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have a greater capacity for re-growing their damaged axons, and under appropriate conditions there is a recovery of function. It has not been possible to put forward a direct and simple explanation of this difference in regenerative capacity. Recent studies, however, give credence to Cajal’s notion that the fault in CNS regeneration lies with the extrinsic environment surrounding the neuron. Such explanation clearly does not encompass lower vertebrates, in particular the fish, whose CNS axons are endowed with a remarkable capacity for spontaneous repair after injury, despite having an extrinsic environment that shares many of the features found in mammalian CNS.

Set out below is a brief description of the components that make up the environment of the CNS and PNS in mammals, and how their reaction to injury is perceived to impact upon the failure and success of axonal regeneration, respectively. This is followed by a detailed analysis of the events that accompany the repair process in the injured goldfish optic nerve, highlighting the environment of the lesion and distal nerve and how each region adapts over a period of several months to accommodate firstly axonal regrowth and later myelination. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural evidence will be presented to show that regeneration in fish optic nerve is accompanied by several events that are common to regeneration in mammalian PNS, and that the CNS environment surrounding the regenerating axons actively supports, rather than inhibits, axonal outgrowth.

7. Glial environment of axons in mammalian CNS

One of the components of the milieu that surrounds an axon in the CNS is astrocytes. During embryonic development, astrocytes act in guiding axon growth and neuronal development (Rakic, 1976; Hatten, 1990). This capacity appears to be lost in the adult, with the consequence that an injury to the CNS induces tissue damage that creates barriers to regeneration. One of the main barriers is the glial scar, which consists primarily of hypertrophied (enlarged/reactive) astrocytes. Reactive astrocytes are perceived to form a physical wall that wards off any further damage to the tissue. The process leads, however, to the formation of the glial scar, beyond which axons cannot regenerate (Reier et al., 1983). Recent studies have sought to identify the molecular constituents of the glial scar that may play an additional role in inhibiting axon regeneration. It is recognised that whilst astrocytes can produce growth promoting molecules, such as laminin, which aid in attachment and migration of neurons during development, it appears that adult astrocytes also produce a heterogeneous class of molecules known as proteoglycans – proteins to which are attached large sugar residues – whose expression increases in the glial scar, and as a result are thought to act as chemical barriers to axon regeneration in the CNS (Asher et al., 2001; Chirezi and Fawcett, 2001).

A second protagonist in axon regeneration failure in the CNS appears to be myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, an idea first proposed by Berry (1982). Studies based on tissue culture assays have shown that oligodendrocytes and at least two different molecules that are associated with oligodendrocyte myelin, lead to the collapse of the growing axon tip, the growth cone (Schwab and Theonen, 1985). In molecular terms, growth cone arrest is attributed to the unfavourable interaction of growth cone receptors with ligands (myelin proteins) that are bound to oligodendrocyte membrane, and that neutralisation of the proteins promotes regeneration in vivo (Schnell and Schwab, 1990). From these and related observations it is concluded that myelin associated molecules are one of the principal causes of failure of regeneration of cut axons in the intact adult CNS (reviewed by Filbin, 2003).

8. Glial environment of axons in mammalian PNS

The extrinsic environment of the PNS, on the other hand, contains neither astrocytes nor oligodendrocytes. Instead, one cell type, the Schwann cell, performs the dual task of axon guidance and myelination. The Schwann cell also produces basal lamina, (cf. laminin in CNS) a protein-rich membrane that surrounds the Schwann cell-axon unit, forming a tubular structure along the entire length of the nerve. Substantial amount of additional matrix, particularly fibrous collagen that imparts tensile strength to the peripheral nerve, is deposited between these tubular structures. The Schwann cell is believed to impart trophic support to the regenerating axon, which extends to its target by adhering to the substrate made up of the matrix molecules, in a recapitulation of the events that take place during development. The cellular and extracellular components are retained during peripheral axon regeneration (reviewed by Martini, 1994); their absence from the CNS has long been thought as the reason why this system lacks the regenerative capacity. To this end, a number of laboratories have recently reported that the usually abortive axonal sprouting near the lesion site in the injured rat optic nerve can be mobilised to trigger a limited axonal regeneration if an autologous peripheral nerve containing viable Schwann cells is anastomosed to the cut end of the optic nerve (Vidal Sanz et al., 1987; Berry et al., 1988a; Keirstead et al.,1989).

9. Glial environment of axons in goldfish optic nerve

Interestingly, failure of axon regeneration in the CNS is not common to all vertebrates. In lower vertebrates, particularly the fish, axon regeneration in the CNS is the norm, and this is accompanied by the recovery of function. Much research has focussed on the visual system of the goldfish in search of a direct explanation as to why it is endowed with the capacity for functional regeneration, especially since it appears that its glial environment is made up of the same agencies, namely astrocytes and oligodendrocytes which are believed to be responsible for the inhibition of regeneration in adult mammalian CNS.

10. The optic nerve as a model for axon regeneration studies.

The optic nerve has been a popular morphological model for the study of central nerve regeneration. It represents a circumscribed unidirectional white matter tract, supported by astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, and composed almost entirely of fibres of one origin, namely optic axons arising from the retinal ganglion cells. In the goldfish, injury of the optic nerve induces an anabolic response in the ganglion cells that is the prelude to the regenerative response. The metabolic response, known as chromatolysis, is associated with increased biosynthesis of cytoskeletal proteins (Grafstein and Murray, 1969; Quitsche and Schechter, 1983; Perry et al., 1985), so-called growth-associated or GAP proteins (Benowitz and Lewis, 1983; Perrone-Bizzozero and Benowitz, 1987) and lipid products in the cell body. GAPs and lipids are transported by the cytoskeletal proteins to the cut end of the axon, where they are incorporated into the membrane of the growth cone (Grafstein, 1986). Such a response by retinal ganglion cells to axotomy is crucial if the damaged axons are to traverse the lesion and reach the brain. In the goldfish, this feat is accomplished through the survival of more than 90% of the axotomised retinal ganglion cells (Murray, 1982). In the frog, retinal ganglion cells also undergo chromatolysis, but only around 50% of retinal ganglion cells survive axotomy and reach the brain; the remainder of the retinal ganglion cells attempt to regenerate but their axons fail to cross the lesion, and consequently die (Dunlop et al., 2002). Significantly, in mammals only a minimal number of damaged axons cross the lesion unaided; virtually all of the axotomised retinal ganglion cells undergo atrophy through programmed cell death or apoptosis (Berry et al., 1988b; Quigley et al., 1995). The programmed cell death is caused by several factors, including absence of chromatolysis, excitotoxicity to glutamate transmitter (Silviera et al., 1994) as well as loss of endogenous and target-derived neurotrophins. Furthermore, a significant number of retinal ganglion cells seem to die because their axons fail to overcome the lesion. The evidence for this comes from studies in which the cut end of rat optic nerve is grafted to a segment of peripheral nerve: axons are able to extend several millimetres beyond the junctional zone, i.e., the lesion, even in the absence of agents that prevent cell death (Vidal-Sanz et al., 1987; Berry at al., 1988a).

The above comparative studies, whilst highlighting the gradation of responses of retinal ganglion cells to axotomy across the vertebrate taxa, also offer a clear indication that survival of axotomised retinal ganglion cells is dependent to an appreciable degree on their axon overcoming a major hurdle – the site of lesion. Rather surprisingly, however, even in regeneration competent systems there has not been a systematic study of the site of lesion, possibly because the region is considered too disorganised for meaningful analyses. We have taken advantage of the recent availability of several specific-antibodies (Nona et al., 1989; 1990; 1992) to examine the cellular composition of the lesion in the goldfish optic nerve, from shortly after optic nerve crush to several months post injury. Our aim has been to discover if endogenous glial cells, or cells arising from the sheath/septae reoccupy the lesion shortly after injury, possibly serving as scaffolding for the regenerating axons to traverse the lesion. In the course of the study it became apparent that instructive changes also take place as the regrowing axons extend beyond the lesion, through the CNS environment of the distal nerve, and these events will also be described. Throughout the study, the term proximal is used to denote that portion of the optic nerve between the eye and the lesion site, and the term distal to denote the nerve between the lesion and the brain.

11. Events that follow a crush to goldfish optic nerve.

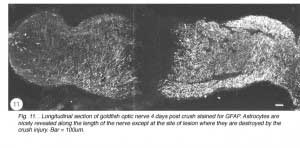

Immediately after the optic nerve has been crushed, and for at least four days thereafter, the lesion appears as a gap between the two nerve stumps, which are held in position by the intact sheath. The tissue-free constriction at the centre of the lesion becomes flanked by a region 200um wide that is devoid of astrocytes, as noted by the absence of GFAP, B7 and Pax-2 immunoreactivity, and contains only a tiny number of cells, most of which are mitotic (BrdU+) and appear to be derived from the sheath/septae where similar cells are present. At this stage, myelin disruption is barely noticeable either in the proximal stump or distally (Nona et al., 1998). It is important to recognise that a lesion of the type described in this study leads not only to the severance of axons, but also to the destruction of local astrocytes. In other words, the continuity of the nerve’s fascicular structure is disrupted as a result of crush injury (Figure 11).

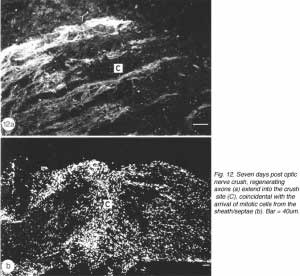

During the following 10 days, there is a large accumulation of mitotic cells in the sheath/septae extending into the core of the lesion (Figure 12) which, nevertheless, remains devoid of astrocytes, unlike in the proximal and distal stumps (and the retina) where astrocytes express an elevated level of GFAP immunoreactivity compared with that in the uninjured nerve – a response that is indicative of injury to CNS tissue.

During the following 10 days, there is a large accumulation of mitotic cells in the sheath/septae extending into the core of the lesion (Figure 12) which, nevertheless, remains devoid of astrocytes, unlike in the proximal and distal stumps (and the retina) where astrocytes express an elevated level of GFAP immunoreactivity compared with that in the uninjured nerve – a response that is indicative of injury to CNS tissue.

The appearance of mitotic cells in the lesion coincides with a strong regrowth of axons (IF145+) from the proximal stump into the lesion, apparently unperturbed by a sea of punctate myelin debris that is scattered throughout the area (Figure 12). However, by 14 days post injury, debris is no longer present in the lesion, which takes on a translucent appearance, in contrast to the opacity of the two nerve stumps (Nona, 1998; Nona et al., 1998).

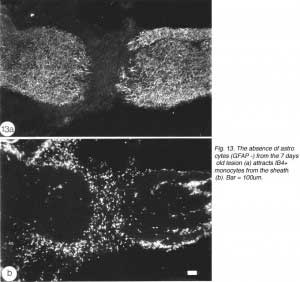

An important question to address relates to the cellularity of the early lesion, and the means by which the regenerating axons traverse the lesion. The cells in the astrocytes-free lesion stain strongly with isolectin IB4 (Figure 13), which has been used as a general marker for microglia/macrophages in rat (Streit et al., 1987) and amphibians (Naujoks-Manyeuffell, 1994).

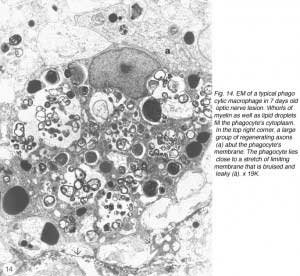

However, in the absence of a more specific marker, a careful study was conducted using EM, with the aim of identifying the cells in the lesion. The study revealed unequivocally that the majority of cells in the early lesion are phagocytic macrophages, as distinct from microglia residing in the distal stump, on account of their morphology as well as the substantial amount of myelin debris present within their cytoplasm (Figure 14).

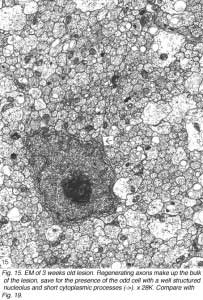

The phagocytes are first seen at 4 days post injury, peaking three days later, coincidental with the appearance of regenerating axons across the lesion. The number of BrdU+ cells also peaks at this time, indicating that the increase in the number of macrophages is due to proliferation as well as recruitment, possibly mediated by mitogenic signals from the necrotic tissue. Indeed, macrophages are confined to the lesion where CNS tissue has been destroyed, and do not infiltrate the degenerating distal stump where CNS environment prevails, an observation that has been confirmed by other workers (Colavincenzo and Levine, 2000). By week 3, the cellularity of the lesion is minimal, phagocytes loaded with myelin debris are noted only in the sheath/septae, and naked axons are the hallmark of the lesion. The cells found among the naked axons have several characteristics that are reminiscent of immature glia cells: a well-structured nucleolus and short cytoplasmic processes that extend into the axons domain (Figure 15). The cells have since been identified as precursor Schwann cells, as will be shown later.

The early appearance of macrophages at the lesion may be important for the outgrowth of axons in several respects. (1) If myelin debris were inhibitory to axonal outgrowth in the fish optic nerve in vivo, as it is in vitro (Sivron et al., 1994; see however, Bastmeyer et al., 1991), then macrophages are playing a crucial role by removing inhibitory molecules from the path of regrowing axons. (2) The outgrowth of the axons may be further enhanced by macrophages releasing growth assisting molecules such as NGF, the expression of which is noted in all of the IB4+ cells in the lesion (Nona, unpublished results). NGF is known to promote regeneration in mammalian PNS (Heumann et al., 1987; Brown et al., 1991). (3) Macrophages may be aiding axonal extension across the lesion in a more direct manner: clusters of regenerating axons ranging from a few to 100 or more per cluster, often associated with a growth cone, are seen abutting the perimeter of the macrophages, which appear to be acting as a bridging substrate or carpet for the growing axons, in a manner akin to that observed in the lesioned optic nerve of the frog (Dunlop et al., 2002). In other words, macrophages in the lesion, in addition to their phagocytic role, also present growth promoting and physical substrate to assist the axons overcome the lesion. Significantly, the absence of astrocytes from the lesion means that endogenous glial cells are not acting as bridges for regenerating axons, as noted also by other workers (Levine, 1991; Blaugrund et al., 1993; Hirsch et al., 1995).

The above results appear to suggest functional parallels between fish optic nerve lesion site and the mammalian PNS, where an injury is characteristically followed by a rapid influx of phagocytic macrophages, as a prelude to successful regeneration (Griffin et al., 1992; Perry and Brown, 1992; Hirschberg and Schwartz, 1995). By contrast, only limited recruitment of macrophages, and by implication debris clearance, is noted in lesioned rat optic nerve (Perry et al., 1987), a phenomenon that has been attributed to inhibitory factors released by resident glial cells (Hirschberg and Schwartz, 1995). To overcome this imbalance, Schwartz and colleagues have introduced monocytes, previously cultured in the presence of fragments of sciatic nerve, into transected optic nerve of rat, to assess the effect of efficient debris clearance by macrophages on axon regeneration. The study showed that fifteen times as many retinal ganglion cell axons regenerated in the treated nerve compared with untreated control nerve, thus confirming the importance of macrophages in axon regeneration (Lazaraov-Spiegler at al., 1996; Rapalino et al., 1998). In the injured fish optic nerve, in addition to the phagocytic macrophages, the early lesion also contains non-phagocytic granular macrophages, a unique class of cells found in goldfish optic nerve (Wolburg, 1981; Battisti et al., 1995). As shown in Figure 7, these cells normally reside in the sheath/septae; their appearance in the lesion is due to the local disruption of nerve’s fascicular pattern and by implication the astrocytic integrity, and strongly suggests that the phagocytic macrophages too are derived from the sheath/septae (see Figure 14). Interestingly, the status of the early lesion as a tissue with PNS characteristics was placed beyond doubt when Schwann cells took up residence in older lesion (see later).

It is instructive to add that the prompt clearance of debris in injured goldfish CNS is not confined to the optic nerve, but also takes place in the optic tract (Nona, 1995) and spinal cord (Nona and Stafford, 1996). And as is the case in the injured optic nerve, regenerating axons in the optic tract and spinal cord use phagocytic cells, not astrocytes, as scaffolding to traverse the lesión.

12. Fish optic nerve vs rat optic nerve.

The apparent ease with which injured axons in fish optic nerve traverse the site of lesion is in stark contrast to the events in injured rat optic nerve, where attempts by the damaged axons to cross the lesion invariably end in failure. As noted earlier, much emphasis has been placed on the role of myelin proteins as one of the principal causes of failure of regeneration of damaged axons in the adult CNS. However, several recent observations favour the contention that inhibition of axon growth by oligodendrocytes/CNS myelin is not the entire answer to the question of why mammalian CNS axons do not regenerate after injury. For example, the myelin inhibitory hypothesis does not explain why axons fail to regenerate through the grey matter, where there is no myelin. Similarly, optic fibres of BW mutant rat, in which both oligodednrocytes and CNS myelin are absent, fail to regenerate in an exclusively astrocytic environment (Berry et al., 1992). Several authorities have, therefore, reopened the “inhibitory” debate, by asserting that astrocytes rather than oligodendrocytes are the main cause of axon regeneration failure in the CNS (Raisman, 2004; Silver and Miller, 2004).

The meticulous studies of axon regeneration in rat optic nerve by Berry and colleagues, have highlighted the fact that astrocytes and mesodermal elements (fibroblasts and collagen) become organised into an impenetrable glia limitans of the scar that envelops the proximal and distal stump ends, largely because injured axons appear unable to initiate an early attempt to regrow, generally within five days of injury (Berry et al., 1996). Furthermore, that injured optic axons can be made to overcome the glial scar and extend into the environment of myelin debris, if provided with sufficient trophic support. By inserting segments of peripheral nerve containing viable Schwann cells as a source of trophic support, into the vitreous and simultaneously crushing the optic nerve, Berry and colleagues have observed that 10% of the injured axons are able to cross the lesion and extend 4 mm into the distal segment (Berry et al., 1996). It is proposed that peripheral nerve implants secrete trophic factors into the vitreous that are then taken up by the retinal ganglion cells and transported to the axon tip, thus stimulating its rapid growth across the lesion before there is a build up of astroglial scar. Earlier studies, in which peripheral nerve containing viable Schwann cells was grafted to the cut end of rat optic nerve, yielded similar results in terms of retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regrowth beyond the site of anastomoses, that is, into the peripheral nerve (Vidal Sanz, et al., 1987; Berry et al., 1988). These results do not argue against the view that glial scarring may, in some way, curtail axonal outgrowth. They do however suggest that the effect of trophic influences derived from viable Schwann cells are capable of nullifying the inhibitory effects on axonal outgrowth exerted by a scar of limited dimension. Put another way, the ability of a cut axon to regrow is dependent on the balance between the intrinsic ability of the axon to regrow and the permissiveness of the environment surrounding it.

In the injured fish optic nerve, the conditions appear to favour retinal ganglion cell survival and vigorous axonal outgrowth in the absence of external manipulations. The clearance of myelin debris is entrusted to phagocytic macrophages whose presence stimulates an early and robust axonal regrowth which ensures that astrocytes around the stump ends, though markedly hypertrophied and showing an elevated expression of proteoglycans (Battisti et al., 1995), do not become organised into an impenetrable limiting membrane. On the contrary, both at the edge of the proximal nerve, and throughout the degenerating distal nerve, the disrupted fascicular pattern of the optic nerve is gradually restored, as the regenerating axons encounter the awaiting astrocytes, in a recapitulation of events occurring in normal development and growth of the fish optic nerve (cf. Scholes et al., 1992).

13. Regeneration in goldfish optic nerve distal to lesión.

By around 10 days post injury, regenerating axons begin to emerge from the lesion proper into the distal nerve to be confronted by an environment dominated by hypertrophied astrocytes, myelin and axonal debris. The progress of the regenerating axons through this apparently chaotic environment is best followed using EM (Nona et al., 1998).

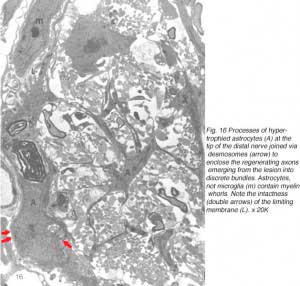

At first, small groups of new axons appear among radial processes of hypertrophied astrocytes where there is also a scatter of myelin debris. Astrocyte processes, connected by desmosomal junctions, form a myriad of irregular loops that enclose the newly arrived axons into loosely organised bundles (Figure 16).

By 14 days, these have swollen into large bundles of tightly fasciculated axons, surrounded and separated from one another by cordons of lamellar astrocyte processes. Myelin debris, which was haphazardly distributed at earlier times, now is neatly confined to the periphery of these fascicles, alongside and within the astrocytic cordon (Figure 17a).

Between 14 and 25 days post crush, the appearance of the distal edge of the nerve is reminiscent of the proximal edge at earlier time post crush: 1) astrocyte radial processes have enwrapped the axon bundles, thus demarcating the new fascicles, and 2) myelin debris is largely confined to the margins of the fascicles alongside the interposing astrocyte processes. More distally, the old fascicular structure is completely lost, and a substantial amount of debris still remains, present mostly within astrocyte processes, with surprisingly little debris seen in microglia, a finding that has been confirmed by other studies (Colavencenzo and Levine, 2000). The early axons that have reached the chiasm are invariably seen in debris-free areas, or enveloped by astrocyte processes.

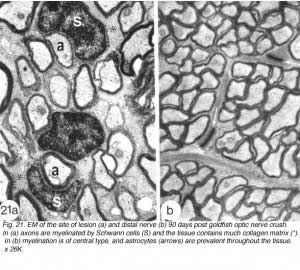

By around 43 days, little myelin debris remains and the cytoarchitecture of the regenerated nerve begins to resemble that of the normal nerve, with astrocyte processes dividing the tissue into glial channels/compartments, thus restoring the fascicular pattern of the nerve. The patterning precedes axon remyelination (Figure 17b), which is known to be a protracted process, taking several weeks for near completion, and is rarely observed before around 40 days post nerve injury, that is, several weeks after the regenerating axons have crossed the lesion (Wolburg, 1981; Battisti et al., 1995; Nona et al., 2000). In this study, there was little evidence of remyelination before around 50 days post crush. By 90 days, however, virtually all of the new axons in the distal nerve are myelinated by oligodendrocytes, much like the normal tissue (Figure 21b), but in total contrast to remyelination in the lesion (see below).

It is important to emphasis that although there are structural similarities between the peripheral nerve and the optic nerve of the goldfish, in that both nerves consist of a multitude of cylindrical tubules or compartments, the mechanisms of axon regeneration in the two systems are quite different. In the regeneration of the peripheral nerve, growth cones are found exclusively in contact with the inner surface of the basal lamina of the Schwann tube (Scherer and Easter, 1984). During regeneration of the optic nerve, however, new axons (this study), preceded by their growth cone (Easter, 1987) are only found deep within astrocyte fascicles, among other axons. This suggests that astrocytes, rather than basal lamina, support axonal growth during regeneration, and this pattern forming interaction with the astrocytes, forming glial channels that exclude the degenerating myelin debris, may greatly facilitate the growth of the many axons that follow (Nona et al., 1998).

In this study it is assumed that the pioneering axons emerging into the distal optic nerve will, in all probability, encounter not only astrocytes but also myelin debris. That this mixed environment appears not to disrupt the progress of regenerating axons owes much to the vigorous growth of the growth cone as well as, perhaps, myelin debris characteristics. In the trout, for example, CNS myelin lacks the mammalian protein PLP, but contains two proteins IP1 and IP2 which are immunologically related to PNS myelin protein P0 (Jeserich et al., 1990). On this basis it may be argued that fish myelin proteins have similar properties to myelin proteins found in the PNS, which are known not to inhibit neurite extension in vitro (Schwab and Theonen, 1985). However, more recent studies have established that CNS myelin in fish does contain proteins that inhibit axonal extension in vitro, much like their mammalian counterparts (Sivron et al., 1994).

14. Myelination of regenerating goldfish optic nerve axons in the lesion by Schwann cells.

So far, much emphasis has been placed on the paucity of cells in general, and that of astrocytes in particular, in the lesion. The substantial number of mitotic cells that accumulate in the lesion by day 7, and identified as macrophages, is much attenuated a week later, as the phagocytes quickly clear the debris and then disperse into the sheath/septae (see above). In the following weeks, the rate of division in the lesion is no greater than in the rest of the nerve.

Consistently, however, a second wave comprising large numbers of dividing BrdU+/S100- cells appear in the lesion at around 43 days post nerve injury (Nona, 1998; Nona et al., 1992; 2000). Over a period of several weeks, the number of dividing cells gradually decreases, to be replaced concomitantly by S100+ cells whose spindly nuclei and bipolar morphology matches precisely that of Schwann cells in the peripheral nerve. By 90 days, BrdU+ cells are virtually absent from the lesion, which, nevertheless, is packed with S100+ cells (Figure 18).

Antibodies to two fish-derived myelin proteins (central myelin 36K, and peripheral/central myelin 6D2; Jeserich and Waehneldt, 1986), have proved invaluable in confirming the identity of these previously unreported cells in the optic nerve lesion (Nona et al., 1992; 2000). In sections from 90 days old optic nerve, 36K antibody fails comprehensively to recognise myelin in the lesion, which is nevertheless flanked by bright central staining in both proximal and distal nerves. 6D2 antibody, on the other hand, recognises myelin in the lesion and throughout the optic nerve. It is noteworthy that the appearance of S100+ cells coincided with the expression of 6D2 in the lesion, with a striking correspondence between the two labels. That the expression of 6D2 heralds the beginning of axonal remylination is supported by studies which show that the earliest expression of myelin-related antigens in dissociated cell population of trout CNS coincides with the first appearance of myelinated fibres in defined brain regions (Jeserich et al., 1990). Our observation are also in agreement with those from the developing mammalian PNS, in which the expression of S100 marks the transition from precursor to mature Schwann cells, and coincides with the commencement of myelination (Jessen and Mirsky, 1999).

Further evidence in support of the identity of the cells in the lesion as Schwann cells comes from ultrastructural studies: Firstly, the cells form a 1:1 association with myelinated axons, and each cell:axon unit is enclosed by basal lamina, thus resembling Schwann cells of the PNS. Secondly, in contrast to the compact arrangement of the tissue in proximal and distal stumps, the lesion contains considerable collagen and extracellular space, characteristic of PNS tissue. Thirdly, the environment in the lesion contains none of the elements, namely astrocytes, that define CNS environment elsewhere in the nerve (Figures 21a).

15. Source of Schwann cells in regenerating goldfish optic nerve.

Although the appearance of Schwann cells in the lesion has been observed in every injured optic nerve studied by the author and his colleagues, the source of the Schwann cells and their arrival in the lesion have only recently been addressed. In normal CNS tissue, ectopic Schwann cells are rarely seen. They are excluded by astrocyte processes that are arranged as a glia limitans, forming a boundary between CNS and PNS. It is, therefore, not unreasonable to suggest that in the present study the colonisation of the lesion by Schwann cells, much as its earlier colonisation by macrophages, is the result of disruption of the astrocytic glia limitans (see Figure 14). Support for this notion comes from studies of optic nerves that have received two or more adjacent lesions, which show that the larger the area over which astrocytes are destroyed, the greater is the Schwann cell invasion. Such correlation between Schwann cell invasion and the extent of astrocytes destruction has also been described in rat spinal cord following local injection of gliotoxic agents (Blakemore, 1975; 1983).

As stated earlier, a characteristic feature of the goldfish optic nerve is that it is interleaved by connective tissue septae, which are an integral part of the nerve sheath. This arrangement brings a network of mesenchymal cells and capillaries within the outline of the fibre array. This poorly understood mix, elsewhere excluded from the interior of the CNS tissue, could well contain cells of neural crest origin and, in the event of glia limitans disruption, the pattern is well deployed to supply them locally as precursor Schwann cells (see Figure 15). In this context it is interesting that ectopic Schwann cells are never observed beyond the nerve-tract boundary – a line that also defines the limit of the reticular astrocytes in the optic nerve (Nona 1995). We have carried out a detailed ultrastructural study of the lesion site to track down the precursor Schwann cell in the goldfish optic nerve.

Careful studies of the injured optic nerve, ranging from 14 days to 3 months old, have confirmed that the younger lesions do indeed contain the occasional cell (Fig, 15) having several elongated cytoplasmic sheets that insinuate between the regenerated naked axons, which they enwrap communally (Figure 19). In this respect, these cells have a striking resemblance to precursor Schwann cells found in the nerve of rat hind leg (see Figure 1 in Jessen et al., 1994). Connective tissue spaces and extracellular matrix are absent from the early lesion, and the tissue here remains compact due to the large number of axons it contains. In older lesions, individual cells are noted in a unitary relationship with an axon, but such encounters are rare prior to around 40 days post lesion.

Consistently, however, the lesions around 50 days old begin to take on characteristics that are unmistakably those of peripheral nerve tissue. Axons in a 1:1 association with cells begin to acquire myelin, and these units are invariably surrounded by collagen matrix that form “rivers” through the tissue (Figure 20).

Consistently, however, the lesions around 50 days old begin to take on characteristics that are unmistakably those of peripheral nerve tissue. Axons in a 1:1 association with cells begin to acquire myelin, and these units are invariably surrounded by collagen matrix that form “rivers” through the tissue (Figure 20).

The delayed differentiation of precursor Schwann cells into myelinating cells corresponds nicely with the late appearance of S100+/6D2+ immunoreactivity in the lesion, which means that both central (discussed earlier) and peripheral myelination commence synchronously. Furthermore, as already described for the distal nerve, myelination in the lesion is also a protracted process. By 90 days, however, myelinating Schwann cells colonise the lesion (Nona et al., 1990; 2000), building a perfect segment of peripheral nerve tissue intercalated into the regenerated visual pathway (Figure 21).

The delayed differentiation of precursor Schwann cells into myelinating cells corresponds nicely with the late appearance of S100+/6D2+ immunoreactivity in the lesion, which means that both central (discussed earlier) and peripheral myelination commence synchronously. Furthermore, as already described for the distal nerve, myelination in the lesion is also a protracted process. By 90 days, however, myelinating Schwann cells colonise the lesion (Nona et al., 1990; 2000), building a perfect segment of peripheral nerve tissue intercalated into the regenerated visual pathway (Figure 21).

16. Thoughts on delayed remyelination in goldfish optic nerve.

We interpret the observations relating to myelin formation in the regenerated fish optic nerve as follows: Schwann cells arise from a small number of continually dividing founder cells that colonise the lesion inconspicuously at an early stage, rather than by massive expansion at a late stage in regeneration. To distinguish between the two possibilities, established Schwann cells were challenged with renewed axonal regrowth from a second optic nerve injury, but again they only began to divide immediately prior to the onset of myelin formation, around 45 days, in synchrony with the peak of Schwann cell division in the new lesion (Nona et al., 2000). The failure of Schwann cells to respond to axotomy is, therefore, in contrast to the prompt response of injured axons in mammalian PNS, which show division at the first appearance of the regenerating axons (Pellegrino and Spencer, 1985). The observations in fish optic nerve, therefore, firmly identify a delayed wave of mitogenic signals occurring several weeks after initial axon outgrowth through the lesion.

The ectopic Schwann cells in the fish optic nerve thus conform to a schedule for myelin formation that is characteristic of CNS in general, whereby oligodendrocyte myelination begins late in development at widely different times in different pathways (Schwab and Schnell, 1989). The lengthy period over which myelination is taking place corresponds with the critical period in optic nerve regeneration when the initial disorderly pattern of axon terminals in the tectum is refined into an accurate point-to-point map (Schmidt, 1990).

Presumably, myelin formation is triggered by target-related changes in individual optic axons that occur at some stage during refinement. During the disorderly process of re-innervating the optic tectum, some axons may be better placed from the outset than others to retract their initial widespread branches into focussed retinotopic arbors: these could be the axons that are myelinated first, while the less well placed axons take longer (Myers and Kageyama, 1999). In other words, myelination proceeds on a fibre-to-fibre basis, and each fibre is continually myelinated throughout its length (Nona et al., 2000). The goldfish visual pathway is well suited to test this hypothesis (Figure 22).

17. Conclusions.

In this commentary we have demonstrated the robustness of fish visual system to manipulations. Severed retinal ganglion cells axons can initiate more than one round of regrowth through a glial environment that shares many of the physical and molecular properties of its counterpart in mammals, but with totally different outcome.

Neither astrocytes nor myelin, both of which are thought to contribute to axon regeneration failure in mammals, impede axonal regeneration in fish optic nerve. On the contrary, astrocytes show much plasticity in response to injury, not by forming a swathe of contiguous impenetrable membrane, but by enwrapping the new axons intimately into bundles and in the process consigning myelin debris to the periphery where it is phagocytosed, not by microglia, but by astrocytes.

However, none of this would be possible were it not for an early and robust response by the damaged axons, aided by invading macrophages which clear the site of injury of debris and act as scaffolding for the regrowing axons. The versatility of fish optic fibres to accommodate more than one type of environment is further demonstrated in older lesions, which Schwann cells colonise to form a perfect PNS tissue intercalated within the CNS tissue. Thus severed fish CNS axons make use of glial cells derived from CNS as well as PNS environments for their repair.

The findings may have implications for axonal regeneration in mammals. It is now recognised that by boosting the rate of phagocytosis in lesioned rat optic nerve, through implantation of reactive macrophages, there is a substantial increase in the number of regenerating axons beyond the lesion. A similar response in noted through the provision of factors derived from Schwann cells that are supplied either to the retinal ganglion cells or applied as implants to the cut end of the axons. Thus, insights from the fish and other regenerating species can provide strategies to overcome the many obstacles of regrowth in mammals, and ultimately lead to successful optic nerve repair in man.

A major unresolved problem in the regrowth of retinal ganglion cells axons is that the initial axotomy results in the death of 90% of retinal ganglion cells. Clearly, substantially more cells must be rescued if a meaningful retinotopic map is to be formed (Sauve et al., 2001). Evolution has already conducted an experiment along these lines, with results of great interest. The optic nerve of reptilians regenerates efficiently, but for some reason refinement of the tectal map fails to occur: the axon terminals persist indefinitely in a diffused array over the tectal surface and the animal never recovers sight (Dunlop et al., 2004).

18. References.

- Asher RA, Morgenster DA, Moon LD, Fawcett JW. Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans: inhibitory components of the glial scar. Prog Brain Res. 2001;132:611–619. [PubMed]

- Bastmeyer M, Beckman M, Schwab ME, Stuermer CAO. Growth of regenerating goldfish axons is inhibited by rat oligodendrocytes and CNS myelin, but not by goldfish optic nerve tract oligodendrocyte-like cells and fish CNS myelin. J Neurosci. 1991;11:626–640. [PubMed]

- Battisti WP, Wang J, Bozek K, Murray M. Macrophages, microglia and astrocytes are rapidly activated after crush injury of the goldfish optic nerve: a light and electron microscopic analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1995;354:306–320. [PubMed]

- Benowitz LI, Lewis ER. Increased transport of 44,000-49,000 Dalton acidic proteins during regeneration of the goldfish optic nerve: a two-dimensional gel analysis. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2153–2163. [PubMed]

- Berry M. Post-injury myelin breakdown products inhibit axonal growth: an hypothesis to explain the failure of axonal regeneration in the mammalian central nervous system. Bibliothetica Anat. 1982;23:1–11.

- Berry M, Hall S, Follows R, Rees L, Gregson N, Sievers J. Response of axons at the site of anastomosis between the optic nerve and cellular or acellular sciatic nerve grafts. J Neurocytol. 1988;17:727–44. [PubMed]

- Berry M, Rees L, Hall S, Yiu P, Sievers J. Optic axons regenerate into sciatic nerve grafts only in the presence of Schwann cells. Brain Res Bull. 1988;20:223–231. [PubMed]

- Berry M, Hall S, Rees L, Carlile J, Wyse JPH. Regeneration of axons in the optic nerve of adult Browman-Wyse (BW) mutant rat. J Neurocytol. 1992;21:426–448.[PubMed]

- Berry M, Carlile J, Hunter A. Peripheral nerve explants grafted into the vitreous body of the eye promote the regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons severed in the optic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1996;25:147–170. [PubMed]

- Bertolini B. Ultrastructure of the spinal cord of the lamprey. J Ultrastruct Res. 1964;11:1–24. [PubMed]

- Bignami A. . Glial cells in the central nervous system. Geneva: FESN-Elsevier. 1991

- Blakemore WF. Remyelination by Schwann cells of axons demyelinated by intraspinal injections of 6-aminonicotinamide. J Neurocytol. 1975;4:745–757. [PubMed]

- Blakemore WF. Remyelination of demyelinated spinal cord axons by Schwann cells. In: Kao CL, Bunge RP, Reier JP, editors. Spinal cord reconstruction. New York: Raven; 1983. p. 281-91.

- Blaugrund E, Cohen I, Hani Y, Schwartz M. Axonal regeneration is associated with glial migration: comparison of the injured optic nerves of fish and rats. J Comp Neurol. 1993;330:105–112. [PubMed]

- Brown MC, Perry VH, Lunn ER, Gordon S, Heumann R. Macrophage dependence of peripheral sensory nerve regeneration: possible involvement of nerve growth factor. Neuron. 1991;6:359–370. [PubMed]

- Cajal S. Ramon Y. 1928. In: Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System. (Translated by May, R.M., 1959). New York. Hafner.

- Cajal SR. In: Thorpe SA, Glickstein M, translators. (1972).The structure of the retina. Springfield (IL): Thomas; 1989.

- Chierzi S, Fawcett JW. Regeneration in the mammalian optic nerve. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2001;19:109–118. [PubMed]

- Colavincenzo J, Levine RL. Myelin debris clearance during Wallerian degeneration in the goldfish visual system. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:47–62. [PubMed]

- Dingwell KS, Holt CE, Harris WA. The multiple decisions made by growth cones of RGCs as they navigate from the retina to the tectum in the Xenopus. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:246–259. [PubMed]

- Dunlop SA, Tennant M, Beazley LD. Extent of retinal ganglion cell death in the frog Litoria moorei after optic nerve regeneration induced by lesions of different sizes. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446:276–287. [PubMed]

- Dunlop SA, Tee LBG, Stirling V, Taylor AL, Runham PB, Barber AB, Kutchling G, Roger J, Roberts JD, Harvey AR, Beazley LD. Failure to restore vision after optic nerve regeneration in reptiles: interspecies variation in response to axotomy. J Comp Neurol. 2004;478:292–305. [PubMed]

- Easter SS, Rusoff AC, Kisk PE. The growth and organisation of the optic nerve and tract in juvenile and adult goldfish. J Neurosci. 1981;1:793–811. [PubMed]

- Easter SS. Retinal axons and the basal lamina. In: Wolff JR et al., editors. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in neural development. Berlin: Springer; 1987. p. 385-96.

- Filbin MT. Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:703–713. [PubMed]

- Fuchs C, Druger RK, Glasgow E, Schechter NJ. Differential expression of keratins in goldfish optic nerve during regeneration. J Comp Neurol. 1994;343:332–340.[PubMed]

- Ghandour MS, Labourdette G, Vicendon G, Gombos G. A biochemical and immunochemical study of S-100 protein in developing rat cerebellum. Dev Neurosci.1981;4:98–109. [PubMed]

- Hatten MB. Astroglia as scaffold for development of the CNS. Semin Neurosci. 1990;2:455–465.

- Grafstein B, Murray M. Transport of protein in goldfish optic nerve during regeneration. Exp Neurol. 1969;25:494–508. [PubMed]

- Grafstein B. The retina as a regeneration organ. In: Adler R, Farber D, editors. The retina–a model for cell biology studies. Part II. London: Academic; 1986. p. 273-335.

- Griffin JW, George R, Laboto C, Williams RT, Yan LC, Glass JD. Macrophage reponses and myelin clearance during Wallerian degeneration: relevance to immune-mediated demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;40:153–166. [PubMed]

- Heumann R, Lindholm D, Bandtlow C, Meyer MS, Radekc MJ, Misko TP, Shooter E, Theonen H. Differential regulation of mRNA encoding nerve growth factor and its receptor in sciatic nerve during development, degeneration and regeneration: role of macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:8735–8739. [PubMed] [Free Full text in PMC]

- Hirsch S, Cahill MA, Stuermer CAO. Fibroblasts at the transection site of the injured goldfish optic nerve and their potential role during retinal axonal regeneration.J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:599–611. [PubMed]

- Hirschberg DL, Schwartz M. Macrophage recruitment to acutely injured central nervous system is inhibited by a resident factor: a basis for an immune-brain barrier.J Neuroimmunol. 1995;61:89–96. [PubMed]

- Jeserich G, Waehneldt TV. Characterisation of antibodies against major fish CNS myelin proteins: immunoblot analysis immunochemical localisation of 36K and IP2 proteins in trout nerve tissue. J Neurosci Res. 1986;15:147–157. [PubMed]

- Jeserich G, Muller A, Jacque C. Developmental expression of myelin proteins by oligodendrocytes in the CNS of trout. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;51:27–34.[PubMed]

- Jessen KR, Brennan A, Morgan AL, Mirsky R, Kent A, Hashimoto Y, Gravrilovic J. The Schwann cell precursor and its fate: a study of cell death and differentiation during gliogenesis in rat embryonic nerves. Neuron. 1994;12:509–527. [PubMed]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Developmental regulation in the Schwann cell lineage. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;468:3–12. [PubMed]

- Keirstead SA, Rasminsky M, Fukuda Y, Carter DA, Aguayo AJ, Vidal-Sanz M. Electrophysiologic responses in hamster superior colliculus evoked by regenerating retinal axons. Science. 1989;246:255–257. [PubMed]

- Kruger L, Maxwell DS. The fine structure of ependymal processes in the teleost optic tectum. Am J Anat. 1966;119:479–497. [PubMed]

- Lazarov-Spiegler O, Solomon AS, Zeev-Brann AB, Hirschberg DL, Lavie V, Schwartz M. Transplantation of activated macrophages overcomes central nervous system regrowth failure. FASEB J. 1996;10:1296–1302. [PubMed]

- Levine RL. Organisation of astrocytes in the visual pathways of the goldfish: an immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:231–246. [PubMed]

- Levine RL. Gliosis during optic fiber regeneration in the goldfish: an immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 1991;312:549–560. [PubMed]

- Ludwin SK, Kosek KC, Eng LE. The topographic organisation of S-100 and GFA proteins in the adult rat brain: and immunohistochemical study using horseradish peroxidase-labelled antibody. J Comp Neurol. 1976;165:197–208. [PubMed]

- Maggs A, Scholes J. Reticular astrocytes in the fish optic nerve: macroglia with epithelial characteristics form an axially repeated lacework pattern to which nodes of Ranvier are apposed. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1600–1614. [PubMed]

- Martini R. Expression and functional roles of neural cell surface molecules and extracellular matrix components during development and regeneration of peripheral nerves. J Neurocytol. 1994;23:1–28. [PubMed]

- Meyer RL, Kageyama GH. Large-scale synaptic errors during map formation by regenerating optic axons in the goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 1999;409:299–312.[PubMed]

- Murray M. A quantitative study of regenerative sprouting by optic axons in goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 1982;209:352–62. [PubMed]

- Naujoks-Manteuffel C, Niemann U. Microglia cells in the brain of Pleurodeles watl (Urodela salamaderia, Salamandridae) after Wallerian degeneration in the primary visual system using Bandeiraea simplicifolia isolectin B4 cytochemistry. Glia. 1994;10:101–113. [PubMed]

- Nona SN, Shehab SAS, Stafford CA, Cronly-Dillon JR. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) from goldfish: its localisation in visual pathway. Glia. 1989;2:189–200.[PubMed]

- Nona SN, Stafford CA, Shehab SAS, Cronly-Dillon JR. A polyclonal antibody to to goldfish neuronal 145kDa intermediate filament protein. Brain Res.1990;524:133–138. [PubMed]

- Nona SN, Stafford CA, Shehab SAS, Cronly-Dillon JR. GFAP as a marker for astrocytes in normal and regenerating goldfish visual system. In: Nona SN, Cronly-Dillon JR, Ferguson M, Stafford CA, editors. Developmental and regeneration of the nervous system. London: Chapman-Hall; 1992. p. 97-108.

- Nona SN, Duncan A, Stafford CA, Maggs A, Jeserich G, Cronly-Dillon JR. Myelination of regenerated axons in goldfish optic nerve by Schwann cells. J Neurocytol.1992;21:391–401. [PubMed]

- Nona SN. Repair by Schwann cells in the regenerating goldfish visual pathway. In: Vernadakis A, Roots B, editors. Neuron-glia interactions during phylogeny. Vol. 2. Totowa (NJ): Humana; 1995. p. 347-65.

- Nona SN, Stafford CA. Glial repair at the lesion site in regenerating goldfish spinal cord: an immunohistochemical study using species specific antibodies. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:350–356. [PubMed]

- Nona SN, Thomlinson AM, Stafford CA. Temporary colonisation of the site of lesion by macrophages is a prelude to the arrival of regenerating axons in the regenerating goldfish optic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1998;27:791–803. [PubMed]

- Nona SN. Invited review: Repair in goldfish central nervous system. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1998;12:1–11. [PubMed]

- Nona SN, Thomlinson AM, Bartlett CA, Scholes J. Schwann cells in the regenerating fish optic nerve: evidence that CNS axons not the glia determine when myelin formation begins. J Neurocytol. 2000;29:285–300. [PubMed]

- Pellegrino RG, Spencer PS. Schwann cell mitotis in response to regenerating peripheral axons in vivo. Brain Res. 1985;341:16–25. [PubMed]

- Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Benowitz LI. Expression of a 48 kilodalton growth associated protein in the goldfish retina. J Neurochem. 1987;48:644–652. [PubMed]

- Perry VH, Brown MC, Gordon S. The macrophage response to central and peripheral nerve injury. A possible role for macrophages in regeneration. J Exp Med.1987;165:1218–1223. [PubMed]

- Perry VH, Brown MC. Role of macrophage in peripheral nerve degeneration and repair. Bioessays. 1992;14:401–416. [PubMed]

- Quigley HA, Nickells RW, Kerrigan LA, Pease ME, Thibault DJ, Zack DJ. Retinal ganglion cell death in experimental glaucoma and after axotomy occurs by apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:774–786. [PubMed]

- Quitsche W, Schechter N. Specific optic nerve proteins during regeneration of the goldfish retinotectal pathway. Brain Res. 1983;258:68–78.

- Rabe H, Koschorech E, Nona SN, Ritz HJ, Jeserich G. Voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels in radial glial cells of trout optic tectum studied by patch clamp analysis and single cell RT-PCR. Glia. 1999;26:221–232. [PubMed]

- Rakic P. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing the shape of neurons and their assembly into neuronal circuits. In: Seeman P, Brown GM, editors. Frontiers in neurology and neuroscience research.Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1976. p. 112-32.

- Reier PJ, Stensaas LJ, Guth L. The astrocyte scar as an impediment to regeneration in central nervous system. In: Kao CC, Bunge RP, Reier PJ, editors. Spinal cord reconstruction. New York: Raven; 1983. p. 163-95.

- Raisman G. Myelin inhibitors: does no mean go? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:157–161. [PubMed]

- Rapalino O, Lazarov-Spiegler O, Agranov E, Katz A, Hadani M, Schwartz M. Implantation of stimulated homologous macrophages results in partial recovery of paraplegic rats. Nat Med. 1998;4:814–821. [PubMed]

- Reichenbach A, Schneider H, Richter W, Reichelt W, Schaaf P. The course of axons within thte postnatal rabbit retina. J Hirnforsch. 1989;30:505–511. [PubMed]

- Rungger-Brandle E, Achtstatter T, Franke WW. An epithelial-type cytoskeleton in a glial cell: astrocytes of amphibian optic nerves contain cytokeratin filaments and are connected by desmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:705–716. [PubMed]

- Sauve Y, Sawai H, Rasminsky M. Topological specificity in reinnervation of the superior colliculus in regenerated retinal ganglion axons in adult hamsters. J Neurosci. 2001;21:951–960. [PubMed]

- Scherer SS, Easter SS. Degenerative and regenerative changes in the trochlear nerve of the goldfish. J Neurocytol. 1984;13:519–565. [PubMed]

- Schmidt JT. Long term potentiation and activity dependent retinotopic sharpening in the regenerating retinotectal projection of the goldfish: common sensitive period and sensitivity to NMDA blockers. J Neurosci. 1990;10:233–246. [PubMed]

- Schmechel DE, Rakic P. A Golgi study of radial glial cells in developing monkey telencephalon: morphogenesis and transformation into astrocytes. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1979;156:115–132. [PubMed]

- Schnell L, Schwab ME. Axonal regeneration in rat spinal cord produced by antibody against myelin associate neurite growth. Nature. 1990;343:269–272.[PubMed]

- Schnitzer J. Astrocytes in mammalian retina. Prog Retinal Res. 1988;7:209–231.

- Scholes J, Maggs A, Dowding AJ. Glial axonal pattern formation in the fish optic nerve. In: Nona SN, Cronly-Dillon JR, Ferguson M, Stafford CA, editors. Development and regeneration of the nervous system. London: Chapman-Hall; 1992. p. 109-43.

- Schwab ME, Theonen H. Dissociate neurons regenerate into sciatic but not optic nerve explants in culture irrespective of neurotrophic factors. J Neurosci.1985;5:2415–2423. [PubMed]

- Schwab ME, Schnell L. Region specific appearance of myelin constituents in the developing rat spinal cord. J Neurocytol. 1989;18:161–169. [PubMed]

- Shehab SS, Stafford CA, Nona SN, Cronly-Dillon JR. Anti-goldfish glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) recognises asrtrocytes from rat CNS. Brain Res.1989;504:343–346. [PubMed]

- Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. [PubMed]

- Silveira LC, Russelakis-Carneiro M, Perry VH. The ganglion cell response to optic nerve injury in the cat: differential responses revealed by neurofibrillar staining. J Neurocytol. 1994;23:75–86. [PubMed]

- Sivron T, Schwab ME, Schwartz M. Presence of growth inhibitors in fish optic nerve myelin: postinjury changes. J Comp Neurol. 1994;343:237–246. [PubMed]

- Stafford CA, Shehab SAS, Nona SN, Cronly-Dillon JR. Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in goldfish optic nerve following injury. Glia. 1990;3:33–42.[PubMed]

- Stevenson JA, Yoon MG. Morphology of radial glia, ependymal cells, and periventricular neurons in the optic tectum of goldfish (Carassius auratus). J Comp Neurol. 1982;205:128–138. [PubMed]

- Streit WJ, Kreutzberg GW. Lectin binding by resting and reactive microglia. J Neurocytol. 1987;16:249–260. [PubMed]

- Stuermer CAO, Bastmeyer M. The retinal axons’ pathfinding to the optic disk. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:197–214. [PubMed]

- Traub P. . Intermediate filaments. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 1985

- Vidal-Sanz M, Bray GM, Villegas-Perez MP, Thanos S, Aguayo AJ. Axonal regeneration and synapse formation in the superior colliculus by retinal ganglion cells in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2894–2909. [PubMed]

- Wolburg H. Axonal transport, degeneration, and regeneration in the visual system of the goldfish. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1981;67:1–94. [PubMed]

The author

Dr Sam (Shmaiel) Nona was born in Northern Mesopotamia (now Iraq). At the age of 17 he gained a scholarship to study in England. He graduated with distinction from The Royal Institute of Chemistry in 1968, and went on to complete his PhD in Chemistry under the direction of Professor R.N. Haszeldine, FRS at the university of Manchester in 1971. After an enjoyable period of research in the field of organic fluorine chemistry he was propelled into neuroscience when he joined Professor John Cronly-Dillon whose group was studying the process of repair in the visual system of lower vertebrates. Dr Nona and his colleagues have created a battery of goldfish-specific antibodies, which they have used with great effect to identify several important stages of axon regeneration in the goldfish visual system. He has enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with Dr John Scholes of UCL, aimed at understanding the behaviour of ectopic Schwann cells in CNS environment. Recently, Dr Nona moved to Sydney, and currently holds the position of Visiting Fellow in the School of Optometry and Vision Science at University of New South Wales, Australia.